I’d like to introduce the world’s largest integrated steelmaking complex, the ArcelorMittal Indiana Harbor steel works in East Chicago.

I say I’d like to – but it’s just too big. Too much. Too hard to grasp. And more importantly, too tightly sealed to public access.

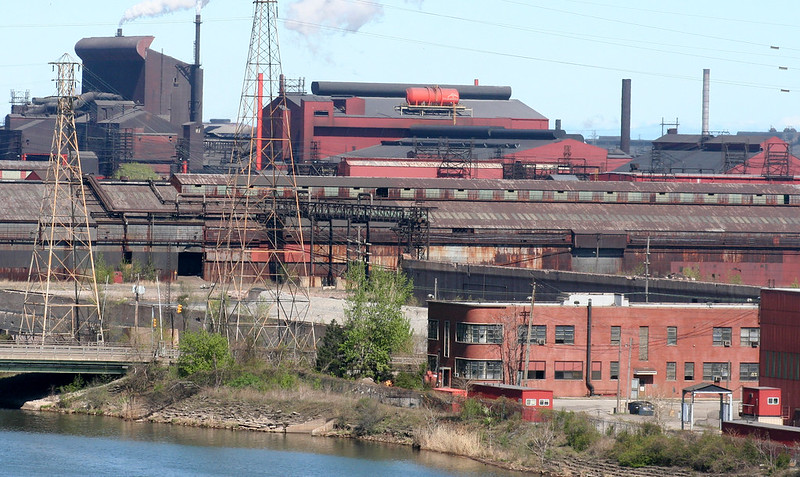

All I can truly offer is a series of stolen glances, quick flashes gained by trooping doggedly around northwest Indiana over the years, over and over – testing the limits of every road, every shoreline, every park, every overpass, every parking lot. I’ve pushed my zoom lenses and my camera’s sensor to their limits, and probably turned the head of every security guard within a mile of the lake’s edge, for glimpses into this astonishing industrial kingdom of ash and fire.

Here I present the results.

One of the facility’s several blast furnaces, where raw ores – fed in at the top, hence all the conveyor belts – are heated and combined into a liquid metal form. AcelorMittal’s website alternately states that there are 3 or 5 blast furnaces on the site.

I cannot say I understand this place, but I am fascinated by it. Flying over it in Bing’s aerial views, the vast size becomes apparent. Hundreds of acres of buildings, jammed one against the next. In true Chicago fashion, they are enormously long, repeating themselves endlessly bay after bay.

What is now ArcelorMittal Indiana Harbor began over a hundred years ago, as the Inland Steel plant. Inland Steel – now most famous for their landmark Modernist headquarters building in downtown Chicago – was formed in 1893, and began development on the Indiana Harbor Canal site in 1902. The business grew over the next 15 years to include a lease on a Minnesota ore mine and a lake freighter division, ensuring in-house control over supply and shipping of raw materials, an integration strategy that would be completed by World War II’s end and last into the 1990s. Across the 20th century, the plant would continuously expand and modernize, while producing a huge variety of goods – from railroad spikes to World War II materiel. Post-war, a large portion of its output went into automobiles. At its peak, 25,000 people worked at the plant. The company was purchased in 1998, becoming Ispat Inland. Mergers in 2005 and 2007 created ArcelorMittal, an international corporation that is the world’s largest steel company and current owners and operators of the facility.

The huge complex is mostly sited on an artificial peninsula jutting out into Lake Michigan, with the Indiana Harbor Canal running down the middle. Many acres are covered with buildings; the site is also criss-crossed with railroad tracks, roads, overpasses, material storage lots, and a huge variety of industrial structures. In the 2010 photograph above, the now-demolished Cline Avenue – aka Indiana State Road 912 – snakes its way around the inland portion of the facility. Marktown is visible at lower left; just out of the frame to the left is the giant BP refinery at Whiting.

The site is also a bottleneck for railroads as they muscle their way into Chicago; at one point, nearly half a dozen rail bridges crossed the canal. Only one remains in full-time service, but it sees heavy use, with multiple freight trains crossing it hourly.

Raw materials arrive primarily by boat; the wide mouth of the canal can handle full-size lake freighters and has docking space for several. Huge ore cranes lining both sides of the canal unload arriving ships.

One result of having such a huge complex is that outdated buildings and equipment are often abandoned in place and may stand for years, untouched, while business proceeds around them. It’s not like there are neighbors to complain! Large expanses of the site may deteriorate for years and even become overgrown.

Above: remains of an abandoned blast furnace alongside the canal in 2004. Already stripped of their support infrastructure, the hearths were dismantled shortly afterwards.

Above: remains of Inland Steel’s coke ovens and by-products processing plant. Inland ceased coke production in 1993, but the abandoned ovens still stand, with grass growing on the roof.

Long-abandoned ramp and trestle alongside Dickey Road. BP’s Whiting refinery looms in the background.

Half-demolished buildings can hang around for years:

An abandoned building in 2004.

The same building – most of it, anyway – in 2013.

Recycling steel is a major part of the contemporary steel business. Gondolas are stored here, full of scrap steel awaiting its fate in the arc furnace. The now-demolished Highway 912 overpass stands at right.

Legions of criss-crossing electrical lines speak to the vast power requirements of the complex.

And did we mention that there’s a significant work of architecture in the midst of all this industrial madness? The main office building on the site is a lovely 1930 work by Graham, Anderson, Probst & White. It’s an Art Deco beauty in red-brown brick, with floral cartouches atop each bay and twin towers punctuating its skyline.

The steel industry has changed dramatically since its last great domestic peak in the 1970s. Automation has vastly reduced the number of workers required to produce a unit of steel, leading to devastating unemployment in mill-dependent towns like nearby Gary. Evolving technologies have rendered many US facilities obsolete, leading to the kind of abandonment seen here and there on the Indiana Harbor campus. And international competition has required steel companies to be agile and flexible to survive. Outsourcing coke production was just one of a number of maneuvers by Inland and its successors to survive the times.

Rolling mill buildings. In these and other buildings, the newly formed steel is pressed or rolled into bars and other shapes of uniform thickness.

Forgotten Chicago offered a tour of the Indiana Harbor Canal in summer 2013, which sailed right through the middle of the plant; no word yet on when a repeat tour might be offered. Till then, I have more photos of the plant at my Flickr space.