One of my favorite Mid Century Chicago decorative motifs is also among the simplest: patterns of overlapping vertical and horizontal bands, usually done in contrasting colors of brick, on the building’s walls. It’s a simple and stylish way to dress up a large wall space with no windows, particularly one on the building’s street frontage. They’re most powerful when used on a completely blank, flat, rectangular wall – a bold mass with a bold pattern inscribed on it. Often the accent brick is a bright color with a glazed finish, contrasting with the matte background brick around it.

These geometric patterns show up on MCM buildings across Chicagoland, but especially on the south side and inner south suburbs. Sadly, I was not able to uncover much about these buildings’ builders or designers, but there are some definite correlations among disparate sites that raise the old question of whether a single designer was repeating their style, or multiple designers were copying one another.

7859 S. Rutherford Street at 79th, Chicago Ridge. Inevitably, those fantastic Mid-Century doors have been replaced by something cheap and inappropriate, some time during 2011-2012. This building is one of a row of four along 79th Street, and the last to retain its original entryway configuration. All four give street addresses for the side streets, rather than for their primary entries along 79th Street.

7859 S. Rutherford Street at 79th, Chicago Ridge. Inevitably, those fantastic Mid-Century doors have been replaced by something cheap and inappropriate, some time during 2011-2012. This building is one of a row of four along 79th Street, and the last to retain its original entryway configuration. All four give street addresses for the side streets, rather than for their primary entries along 79th Street.

10200, 10216, 10232 S. Crawford (aka Pulaski) Road, Oak Lawn – opened in September 1960, this trio of breezeway apartment buildings features a blank wall at the street, providing some measure of protection against the noise of busy Pulaski (aka Crawford); the geometric pattern serves as adornment for what would otherwise be an unfriendly gesture toward the street. These apartments are located only a block from Saint Xavier University and are home to many students.

10200, 10216, 10232 S. Crawford (aka Pulaski) Road, Oak Lawn – opened in September 1960, this trio of breezeway apartment buildings features a blank wall at the street, providing some measure of protection against the noise of busy Pulaski (aka Crawford); the geometric pattern serves as adornment for what would otherwise be an unfriendly gesture toward the street. These apartments are located only a block from Saint Xavier University and are home to many students.  The backs of the same buildings features simple vertical stripes in a corresponding spot facing the alley:

The backs of the same buildings features simple vertical stripes in a corresponding spot facing the alley:

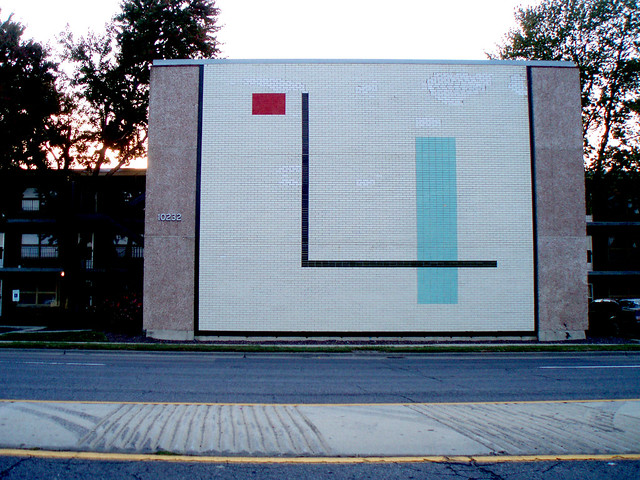

The Riviera Apartments – 9739 S. Kedzie / 9732-9742 S. Troy Avenue, Evergreen Park. Opened 1962. Another breezeway building, with ornamental patterns on the end walls and the sheltered exterior stairwells. Large light blue band, small red rectangle, connecting black stripes – if it is not the same designer as the Crawford buildings, then it’s at least someone who noticed them.

The Riviera Apartments – 9739 S. Kedzie / 9732-9742 S. Troy Avenue, Evergreen Park. Opened 1962. Another breezeway building, with ornamental patterns on the end walls and the sheltered exterior stairwells. Large light blue band, small red rectangle, connecting black stripes – if it is not the same designer as the Crawford buildings, then it’s at least someone who noticed them.

1436 W. Farwell Avenue, Rogers Park – Chicago, built by 1964

1436 W. Farwell Avenue, Rogers Park – Chicago, built by 1964

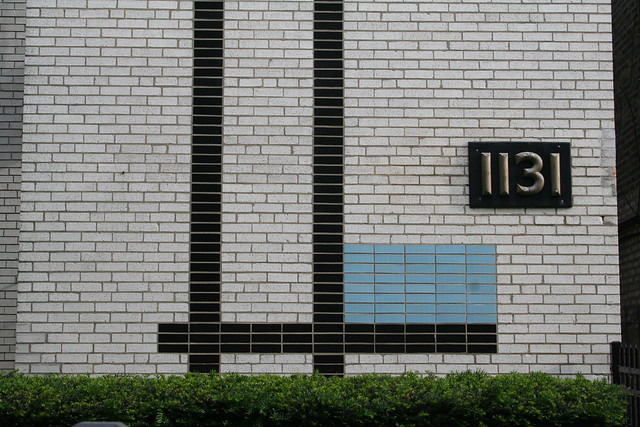

1125-1131 W. Lunt Avenue, Rogers Park – Chicago – opened 1963, replacing an “8 room brick” house that had stood on the lot previously. Developed by L & L Builders as luxury condominiums, when condos were a brand new commodity. The developers, apparently unaware of the doings down at south Kedzie, billed this building as “The Riviera Condominium at the Lake”. (Or maybe they knew all too well, but figured nobody from that deep on the south side would ever venture up this far on the north side!)

1125-1131 W. Lunt Avenue, Rogers Park – Chicago – opened 1963, replacing an “8 room brick” house that had stood on the lot previously. Developed by L & L Builders as luxury condominiums, when condos were a brand new commodity. The developers, apparently unaware of the doings down at south Kedzie, billed this building as “The Riviera Condominium at the Lake”. (Or maybe they knew all too well, but figured nobody from that deep on the south side would ever venture up this far on the north side!)

Deanville Condos at 9105-9111 S. Roberts Road, Oak Lawn – a pair of back-to-back walkup buildings with lower-level garages between them. Here, the vertical band is made of lava rock. Seemingly of a later vintage than the previous buildings, this pair also makes dramatic use of a quasi-mansard roof over the entryways.

Deanville Condos at 9105-9111 S. Roberts Road, Oak Lawn – a pair of back-to-back walkup buildings with lower-level garages between them. Here, the vertical band is made of lava rock. Seemingly of a later vintage than the previous buildings, this pair also makes dramatic use of a quasi-mansard roof over the entryways.

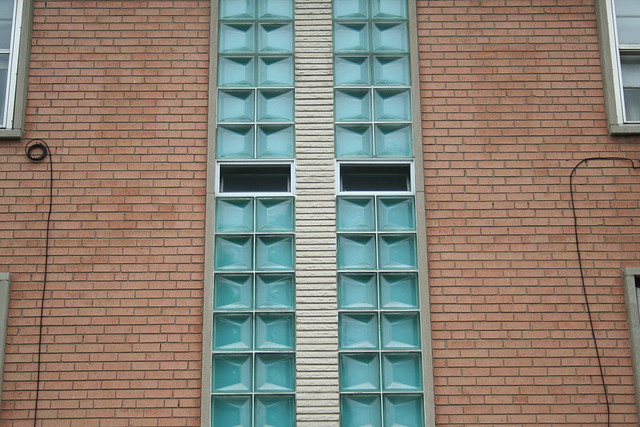

6616 S. Stewart Avenue, Englewood – Chicago. The entryway is marked by a pattern of colored geometric glass block.

6616 S. Stewart Avenue, Englewood – Chicago. The entryway is marked by a pattern of colored geometric glass block.

2030 N. Cleveland Avenue, Lincoln Park – Chicago, opened 1963. Perhaps the simplest possible iteration of the motif, but accented with a grid of raised bricks. The raised brick grid is itself another common Mid Century architectural motif that appears on many buildings across the region.

2030 N. Cleveland Avenue, Lincoln Park – Chicago, opened 1963. Perhaps the simplest possible iteration of the motif, but accented with a grid of raised bricks. The raised brick grid is itself another common Mid Century architectural motif that appears on many buildings across the region.

5439 S. 55th Avenue at 25th Street, Cicero – a unique example that uses concrete panels to form its decorative pattern.

5439 S. 55th Avenue at 25th Street, Cicero – a unique example that uses concrete panels to form its decorative pattern.

4343 W. 95th Street at Kostner, Oak Lawn, opened 1963. A variation on the theme, with thicker vertical bands and glass block accents. The color pattern is very similar to the alley wall of the Crawford/Pulaski buildings.

4343 W. 95th Street at Kostner, Oak Lawn, opened 1963. A variation on the theme, with thicker vertical bands and glass block accents. The color pattern is very similar to the alley wall of the Crawford/Pulaski buildings.

Some designs dispensed with the horizontal accents altogether, instead using a simple column of stacked brick banding.

9600? -9610? N. Greenwood Avenue, Niles – almost certainly the same builder as the previous example. The style is startlingly similar to that used on S. Harlem Avenue by Western Builders.

9600? -9610? N. Greenwood Avenue, Niles – almost certainly the same builder as the previous example. The style is startlingly similar to that used on S. Harlem Avenue by Western Builders.

10425 & 10433 S. Longwood Lane, Oak Lawn – again, top to bottom vertical brick bands on a blank sidewall.

10425 & 10433 S. Longwood Lane, Oak Lawn – again, top to bottom vertical brick bands on a blank sidewall.