Head west out of Chicago on Cermak Road, and at first you may think you’ve come to the end of anything interesting. The first thing to greet your eyes after you cross the city boundary into Cicero is a series of bland strip malls. Nothing could be further from the truth, though. Once you cross Central Avenue, Cermak has many wonders in store as it cruises west through the inner-ring suburbs of Cicero and Berwyn.

Cermak’s buildings gradually transition from pre-War revival and eclectic, to Mid-Century styles. While grand commercial buildings from before World War II are scattered along the Cicero stretch of the road and and into eastern Berwyn – there is no visible transition at the political boundary – the Mid-Century buildings are primarily concentrated in western Berwyn, towards Harlem Avenue.  Berwyn Western Plumbing, 7100 W. Cermak Road, Berwyn – open by October 1962. Two projecting sun shades with two walls of almost continuous glass between them – an ideal box for displaying a vendor’s wares. With the namesake business having relocated elsewhere, this building’s future is currently up in the air.

Berwyn Western Plumbing, 7100 W. Cermak Road, Berwyn – open by October 1962. Two projecting sun shades with two walls of almost continuous glass between them – an ideal box for displaying a vendor’s wares. With the namesake business having relocated elsewhere, this building’s future is currently up in the air.

Rosicky’s National Cleaners, 5818 W. Cermak Road, Cicero. Open by 1966.

Rosicky’s National Cleaners, 5818 W. Cermak Road, Cicero. Open by 1966.

Laundry World, 6947 Cermak Road, Berwyn – present at this spot since the 1990s. The sign is recycled from Color Tile, the previous occupant, who moved in in 1978 and stayed at least through 1990. It’s not clear when the building was originally built.

7008 Cermak Road – The Back Center, Berwyn. Alternately known as the West Suburban Chiropractic Clinic, the business has operated here since 1984. No word on its original life, but the high windows make a doctor’s office seem like a decent bet; mid-1960s seems a likely construction date. A recent “remodeling” has removed the primary points of interest, including the folded-plate canopy and the stacked stone panel at the ground floor.

7008 Cermak Road – The Back Center, Berwyn. Alternately known as the West Suburban Chiropractic Clinic, the business has operated here since 1984. No word on its original life, but the high windows make a doctor’s office seem like a decent bet; mid-1960s seems a likely construction date. A recent “remodeling” has removed the primary points of interest, including the folded-plate canopy and the stacked stone panel at the ground floor.

6534 W. Cermak Road, Berwyn – General Dentistry. Two buildings of red Roman brick with limestone banding. The latter, in particular, is a powerful yet simple geometric composition.

6534 W. Cermak Road, Berwyn – General Dentistry. Two buildings of red Roman brick with limestone banding. The latter, in particular, is a powerful yet simple geometric composition.

6913 W. Cermak Road, Berwyn. The vertical stripe/flag element at left is the primary point of “flare”; the rest of the building is stock 1950s components – orange-blonde brick, limestone banding, bottle glass and metal spandrel panels on the stairwell, and ribbons of metal-framed windows.

6913 W. Cermak Road, Berwyn. The vertical stripe/flag element at left is the primary point of “flare”; the rest of the building is stock 1950s components – orange-blonde brick, limestone banding, bottle glass and metal spandrel panels on the stairwell, and ribbons of metal-framed windows.

Kenilworth Arms Apartments, 6850 W. Cermak Road, Berwyn – a 1959 building by George V. Jerutis & Associates builders, who will be covered in an upcoming post. This one features the glazed baby blue brick which appears on dozens of north side apartments, and an offset grid of projecting bricks on the otherwise blank end wall.

Kenilworth Arms Apartments, 6850 W. Cermak Road, Berwyn – a 1959 building by George V. Jerutis & Associates builders, who will be covered in an upcoming post. This one features the glazed baby blue brick which appears on dozens of north side apartments, and an offset grid of projecting bricks on the otherwise blank end wall.

Bank of America – 5801 W. Cermak Road, Cicero. Originally the Western National Bank of Cicero, a bank founded in 1913. They moved to this, their new location, in May 1960, vacating a NeoClassical building which still stands two blocks east.

Bank of America – 5801 W. Cermak Road, Cicero. Originally the Western National Bank of Cicero, a bank founded in 1913. They moved to this, their new location, in May 1960, vacating a NeoClassical building which still stands two blocks east.

6901 W. Cermak Road, Berwyn – a mixed-use residential/commercial building, opened in 1957. Among the first ground floor tenants was a Niagra massage chair showroom.

Sharon Beauty Supply – 5817 W. Cermak Road, Cicero, 1959 – originally Clyde Savings and Loan Association, founded in 1914. The left-most portion of the building dates back at lest to the 1940s; the current look dates to a 1958 remodeling designed by Chicago Bank Building and Engineering Company, which extended the building west to the corner. The remodeled building opened in January 1959.

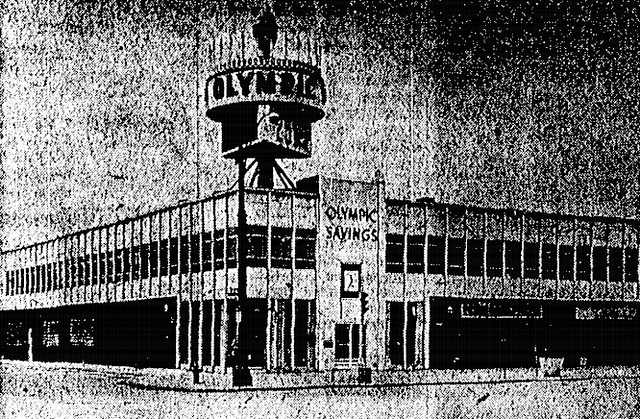

Charter One Bank – 6201 W. Cermak Road, Berwyn – a pre-war building remodeled in the International Style. Originally Olympic Federal Savings and Loan Bank, founded in 1937, the building was expanded and remodeled in 1962, opening in June. The post-remodel building sported a tall round sign over the corner.

Charter One Bank – 6201 W. Cermak Road, Berwyn – a pre-war building remodeled in the International Style. Originally Olympic Federal Savings and Loan Bank, founded in 1937, the building was expanded and remodeled in 1962, opening in June. The post-remodel building sported a tall round sign over the corner.

BMO Harris Bank – 6655 W. Cermak Road, Berwyn, 1957 – originally Lincoln Federal Savings and Loan. Angled walls of flagstone, alternating with metal panel spandrels and a storefront system, as well as sunshade fins, mark it as a high Mid-Century design. See a 1958 postcard view of it in its original glory here, just after it opened. The bank had previously been Lombard Bank, but a custodian working there passed along his interest in President Lincoln to the bank’s president – who changed the company’s name, had two statues of the President commissioned for the property, and included a Lincoln library in the new building.

BMO Harris Bank – 6655 W. Cermak Road, Berwyn, 1957 – originally Lincoln Federal Savings and Loan. Angled walls of flagstone, alternating with metal panel spandrels and a storefront system, as well as sunshade fins, mark it as a high Mid-Century design. See a 1958 postcard view of it in its original glory here, just after it opened. The bank had previously been Lombard Bank, but a custodian working there passed along his interest in President Lincoln to the bank’s president – who changed the company’s name, had two statues of the President commissioned for the property, and included a Lincoln library in the new building.