Back in 2010, I wrote a short post about the Sullivanesque style as it commonly manifests around Chicago – in the form of small commercial buildings decorated with catalog terra cotta ornament designed in Louis Sullivan’s ornamental style. I think that I wrote with some trepidation, the unease that comes when writing seriously about something that the architectural “establishment” dismisses as unimportant (see also: the 4 Plus 1.)

I should know better! The whole point of this blog (and of many others like it around the country) is to delve into the obscure, to explore the “unimportant”. In fact I would hail that as a great accomplishment of the current generation of preservationists, architectural historians, writers and photographers – to elevate things like roadside architecture and vernacular styles and make a serious accounting of them; not to be bound and constrained by the standards of high style that generally get buildings into magazines and guide books.

This point was driven home to me recently by Ronald Schmitt’s excellent work, Sullivanesque (2001.) Schmitt writes not only about Sullivan and his serious contemporaries (Purcell & Elmslie, Henry John Klutho, Trost and Trost, and many others), but also explores the common buildings on Chicago’s commercial streets that were enlivened by the stock terra cotta designs inspired by Sullivan’s works, manufactured in bulk by Midland Terra Cotta Company and a couple of competitors. He points out that in many cases these were quite skillfully applied, and if they were not quite in keeping with Sullivan’s philosophy, they at least in line with some of his formal principles. Let’s take a look!

6634 Cermak Road, Berwyn – Vesecky’s Bakery. 1922. The ornament at the roofline builds to a peak, accentuating the building’s center line. Below, a corniceline suggests the limits of the 2nd floor and roof behind the parapet wall.

3261 N. Milwaukee Avenue – an annex to Kozy’s Cyclery. 1925, architect A.M. Ruttenburg. The roofline crest is heavily based on Midland Terra Cotta Company’s “Store Building Design No. 1.” From the roofline down, the importance of the central main entrance is emphasized. At the door, anomalous Beaux Arts details are used, making this building a bit of a hybrid. The vertical entry/pier assembly overlays horizontal bands that delineate the floors, parapet and roof.

3015 N. Milwaukee Avenue – originally M. Shooman Building; today, Polskie Centrum Medyczne. 1922, architect Rissman & Hirschfield, with stock terra cotta from the Northwestern Terra Cotta Company. Horizontal bands of small, repeating blocks with a relatively simple design delineate the floors and emphasize the long, horizontal nature of this two-story commercial building in Avondale. At the street corner, a concentration of medallions, vertical bands, and roofline capstones emphasize the importance of the entry. Schmitt notes that the ornamental medallion on the long face of the building is derived from a Purcell & Elmslie bank in Rhinelander, Wisconsin.

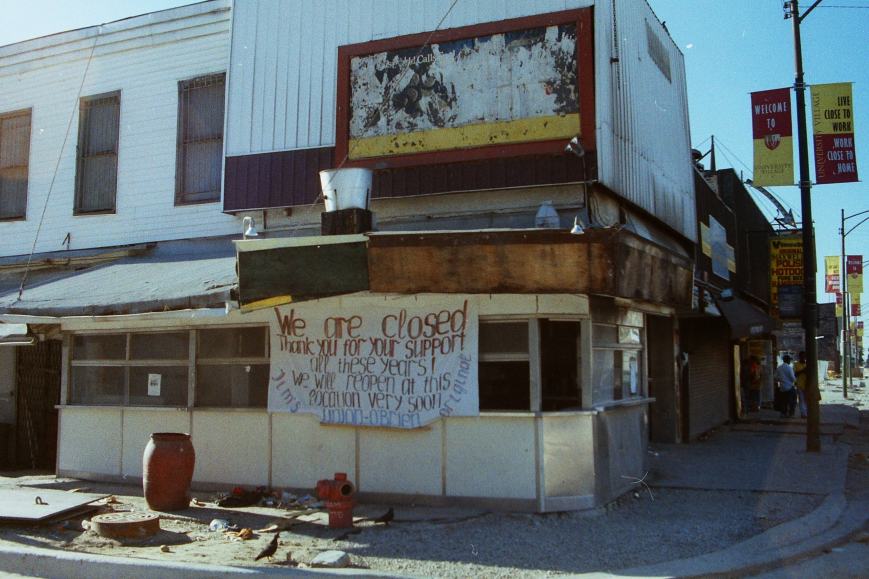

6508-10 S. Halsted Street, Englewood – 1917, architct A.G. Lund. Two storefronts are neatly and clearly called out by the ornament along the roof parapet.

3752-58 W. Montrose at Hamlin – 1925, architect Maurice L. Bein. Medallions punctuate the roofline.

2129 W. Cermak, Little Village – Rubin Brothers Building. 1923, architect A.L. Himelblau.

The George Valhackis Building – 81st and Halsted. 1922, architect Charles J. Crotz. Stock terra cotta from Midland Terra Cotta Co. Medallions demarcate the corner storefront, the various apartment stair entries, and the end of the building. Horizontal bands contain the row of 2nd-story windows.

3445-49 W. Irving Park Road. 1925, architect A.L. Himelblau. Midland Terra Cotta Co terra cotta. The central medallion was Midland catalog item #4508 and appears frequently across Chicago.

3508-12 W. 26th Street, Little Village. 1923, architect Charles Vedra. Medallion 4508 again!

3500 N. Cicero Avenue – originally the Charles Andrews Store. 1925, architect Jens J. Jensen. The roofline of this building is repeatedly punctuated by Midland medallion 4508. Other stock pieces surround it, arranged in configurations suggested by the terra cotta manufacturer themselves. This arrangement of the medallion and its surrounding accents, for example, is directly drawn from Store Buildings Design No. 1 on plate 47 of the Midland Terra Cotta catalog of the early 1920s.