On the 4100 block of West Madison Street, a trio of commercial buildings in the Gothic Revival mode:

From left to right, they are:

- 4138 W. Madison Street – most recently Westgate Funeral Home

- 4132 W. Madison Street – Garfield Counseling Center

- 4128 W. Madison Street – vacant and covered in an melange of overlapping signs

The little two-story funeral home is quite overshadowed by its larger neighbors, but harmonizes perfectly with them. It is Tudor Gothic by vintage, with a two-toned material pallet of red brick and cream terra cotta. Th ornament includes faux quoins of stone at the windows, crenelations along the roofline, and tiny blind arcades of cusped arches in terra cotta, along the outer piers and above the main windows.

Opened by 1927, the funeral chapel here did a steady business for five decades. In the 1970s, the business there was the Baldridge Funeral Home; in the 1990s, the Westgate Funeral Home, whose signs still adorn ground floor canopies. The commercial portion of the building is shuttered today. The narrow building runs the full depth of the block; the Cook County Assessor’s database says it contains three apartments and a garage – where it all fits is a bit of a mystery.

Next door is 4132 W. Madison Street, a four story building with a Gothic-ornamented facade in creamy terra cotta. Four slender piers, capped by faux statuary niche canopies, demarcate three bays. Double rows of blind pointed arches fill the spaces between windows and march across the roofline, giving the facade a busy, heavily shadowed appearance. The original ground floor design is long lost.

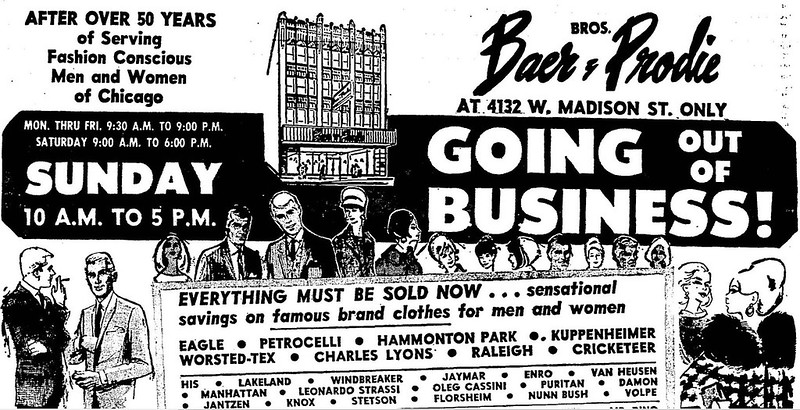

No definitive word on the architects or date of construction, but 1928 is a good bet. That’s the year that Joseph Marschak Sons Furniture began appearing in ads with this address. By 1948, it was owned by the Amber Furniture Company – who had a long run in the building next door – and by 1951, it had been taken over by Baer Brothers & Prodie. They in turn went out of business in 1967; the building housed the Erie Clothing Company for a few years.

By 1973, it was occupied by Debbie’s School of Beauty Culture. In 1980 the school became a subsidiary of Johnson Products, sellers of cosmetics and hair care products, and began developing its own line of cosmetics. The school would later expand to five locations around the city and eleven more in other states. The company eventually moved to Houston, but their fading green-and-yellow painted sign still remains on the building’s brick party wall.

By 1987, the building was home to the Garfield Counseling Center, an outpost in the struggle against the drug abuse which had swept over the neighborhood; in the early 90s, it ran a group home for women trying to break drug habits. The agency operated from at least 1987 and continues today.

4128 Madison has the most complex decorative program of the trio. Its surviving second floor facade gives some hints as to what the first floor might have originally look liked like, with ornamentally framed windows. Above, three floors of Gothic terra cotta with a faint greenish tint rise to the sky. Four carved bosses in the form of grumpy looking grotesques support the four major piers. The piers are capped with pinnacles, seemingly truncated at the roofline. The spandrel panels, however, are where the real action is: they are laden with heraldic shields, fleur-de-lis panels, a yin-yang shape I’m going to tentatively call a doublefoil, and bits of floral carving.

Along the roofline runs a row of large, elaborate blind trefoil or cusped arches adorned with crockets, capped with a row of smaller blind trefoil arches, further capped with a twin parapet cap with a shield motif. It’s quite an extravaganza of terra cotta.

Again, my research came up empty on date, architect, original occupant, and anything about that long-lost vertical sign; I’m taking a guess of 1929.

ETA: the demolished Marbro Theater was nearby – and so Cinema Treasures offers up a distant view of this block when new. The giant sign on this building isn’t legible; behind it, a smaller, similar sign for Marschak Sons Furniture next door can be seen.

The building first appears in the Tribune through 1930 ads for Straus & Schram, a furniture refurbishing business. Straus-Schram was bought out by Spiegel in 1945, who promptly opened a new home store at this location on October 13 of that year, complementing their clothing store down the street at 4020 W. Madison. Spiegel was a heavy advertiser who ran weekly ads for years, selling televisions, washers and dryers, sofas, and all manner of mid-century furniture, until quitting the retail furniture business in 1954 to focus on their mail order catalog sales.

Amber Furniture was the next occupant, taking over by 1955. Their run didn’t end well; in 1961, a public auction was held of all the store’s inventory and equipment. The vacant storefront was used as a Civil Defense information center for a while that year, at the height of Cold War nuclear fears, distributing information on “first aid, home protection, fallout, and other survival information.”

The store was still vacant in December 1963 when a team of robbers entered it, cut a hole through three and a half feet of brick and concrete walls into Baer Brothers & Prodie next door, and stole 750 suits. The robbers were caught in the act when a security patrolman spotted one of them in the store, prompting an escape attempt and police pursuit that ended with a car crash and three of the four in custody.

By 1968, the shuttered Amber Furniture had been replaced by *E*mber furniture, who almost certainly chose their name based on the economy of altering the exterior signs the least amount possible. This store had it going on – they had their own slick soul-styled promo 45, “The Ember Song” by Sidney Barnes in 1969, now widely available again thanks to the magic of YouTube. Give it a listen and feel the vibe of late 1960s Chicago.

Alas, Ember was not forever, and the store disappeared from the Tribune after 1983. 4128 Madison was subsequently absorbed by its neighbor, Debbie’s School of Beauty Culture, whose faded blue and yellow logo is one of several overlapping painted signs still visible on the storefront today. “Amber Furniture – Since 1872” can also be made out in red, and a third occupant’s lettering in white is also visible. Tattered signs in the windows still advertise long-ago furniture lines, while the equally tattered storefront and facade signs are barely legible through the melange of paint and letters. Even the 2nd floor windows still bear the painted logo of a “Family Dental Offices”. The vertical facade sign, meanwhile, still reads “May” and “Easy Credit Terms”, along with a painted-over section I have not been able to decipher. The building is apparently vacant, though some facade work was done in 2008; despite an ancient banner hanging from its signage, it’s no longer listed as for sale online.

Research log, 4138:

1924 – Ben Gross Jewelers, from December 14th Tribune ad – likely an earlier building

1927 – funeral home chapel – from July 21st Tribune death notices, for George D. Fletcher

1971 – last appearance in Death notices

1978 – Baldridge Funeral Home – from April 9, 1978 Tribune column

1997 – Westgate Funeral Home – from Jan 3, 1997 Tribune obituary

Now closed – per Yelp

Research log, 4132:

1928 – Joseph Marschaks Sons furniture – Oct 7 1928 display ad for Chase Velmo mohair upholstery; May 4 1930 display ad for Vanity Fair mattresses – through 1950, Jun 25 diplay ad for Arrow Sport Shirts

1950 – October 1950 – address appears in classifieds 2x

1948 – Amber Furniture Company – Dec 5 1948 display ad for Thor Gladiron

1951 – Baer Brothers & Prodie – Apr 15 1951 display ad for Cricketeer Sport Coats

1967 – Baer Brothers & Prodie goes out of business – display ad Jan 26, Feb 23

1967 – Erie Clothing Company – Dec. 10 display ad for Florsheim dress shoes

1973 – Debbie’s School of Beauty Culture – Feb 15 1973 feature article.

Research log, 4128:

Straus & Schram – Apr 6 1930 Tribune display ad for Vanity Fair mattresses (also includes their competitors Joseph Marschaks Sons, right next door); Nov. 18 1940 Tribune display ad; Dec 6 1944 display ad; Feb 25 1945 display ad – last one.

Spiegel bought out Straus-Schram in 1945 (article, Jan 19 1945)

Spiegel Store – Opend October 13, 1945 (display ad, Oct. 12.). Ran weekly partial or full page display ads for years. Goes out of the Chicago furniture business – display ad Sep 2, 1954

Amber Furniture – display ad Feb 27 1955 – newly opened

Apr 10, 1961 – public auction of inventory and store equipment. (notice Apr 9 1961). T

Civil Defense information center – article, Oct 22 1961