9801-9811 S. Kedzie Avenue, Evergreen Park

In the 1960s, Chicago builders loved do to the same thing over and over and over. You’ll find the same architectural elements on buildings scattered all across the city and its suburbs. One of my old favorites: baby blue glazed brick panels, accents and piers, laid in a stacked bond, on a background of cream, beige or tan brick in running bond. It’s used on dozens of mid-century apartment buildings from Evanston to Burbank and beyond; there is a particularly heavy concentration of them in Rogers Park and West Ridge.

Here we’ll look at a group of a dozen or so that share many distinctive elements: corner piers; rectangular ornamental groups of blue brick, sometimes outlined in limestone; sculpted glass blocks; long, vertical, open rectangles of blue brick with single blue bricks floating in the center; and windows grouped into horizontal bands by limestone surrounds, with the intervening space filled by blue brick.

Whether you just skim the pictures or read every detail, bear in mind the old question I’ve raised again and again on this blog: was it one designer cranking out variations on a theme, or was it multiple designers copying and adapting ideas from each other?

SPOILERS: I found almost no evidence of a common point of origin. However, at best I have only the names of “builders” – which could simply mean the contractor who constructed the building using plans from an independent architect, or a design-build development company with an in-house architect, or even a real estate development company who contracted out all aspects of design and construction to others. It’s entirely possible that a single architect sold drawings to multiple developers and construction companies, and equally possible that several architects swiped details from one another. Several “builders” were responsible for multiple similarly-styled buildings on the list, but multiple builders can also seen using the same details and styles as each other.

You can see most of the basic decorative elements on our first example, below:

2740 W. Pratt, West Ridge – Chicago. David W. Schultz Co., builder; opened by 1965.

Vertical piers of blue brick punctuate the building’s bays. Decorative elements include the open rectangle of blue brick above the entrance – a motif found on several other buildings around the Rogers Park area, in a variety of brick colors. A large section of blank wall is dressed up with a grid of square blue panels floating on a field of cream brick.

1322 W. Chase Avenue, Rogers Park – Chicago. Opened 1965, by Birger Construction Co., replacing a converted house previously on the site. Birger also did an apartment building at 7621 N. Sheridan that uses the same corner-pier vocabulary, but in reddish-orange brick.

This building and the previous one share similar entry detailing as well as the blue corner piers. The “tower” – a raised bay marked by colored piers on both sides – lends interest to the building’s massing.

6116 N. Hermitage Avenue, opened 1964, with studio, 1- and 2-bedroom apartments; operated at the time by the McCarthy Management Corporation. No word on the builder.

This is a third building with corner piers. Sculpted glass block marks the entryway, as well as a tiny folded plate canopy. It also shares the same “tower” massing as the previous building, as well as nearly-identical window treatment – windows rimmed by a limestone band, with blue brick in the surrounded wall space.

4850-4856 N. Paulina Avenue – opened by 1966, by Luna Construction Co., replacing a house on the site (previously home to a family whose four sons all served in World War I.)

A U-shaped courtyard building. The piers, the open rectangle, the folded plate entry canopy, and the banded windows all recur. There’s also a band of colored brick near the roofline, looking a bit like a sweatband on a jogger’s forehead which becomes a cross motif at the courtyard.

7256 N. Bell, Rogers Park – Chicago. J. & H. Construction Co. builders, 1967.

Piers and a grid of squares recur from previous buildings. The balcony railings are similar to those at our next stop…

7241 N. Claremont Avenue, West Ridge – Chicago. Opened in 1962, replacing a 4-unit apartment building on the same site.

In addition to the prominent blue corner pier and “tower” massing, banded windows, outlined rectangles of stacked-bond brick, and sculpted glass block modules over the entryway, this one features lovely matching metal balcony railings. The entry canopy is probably not the original. If my dates are all correct, this would seem to be the prototype for the others in this group.

The vertical bands of glass block over the entryway recur on our next two buildings:

1535 W. Touhy, Rogers Park – Chicago. Open by 1968, possibly by 1965.

Piers, banded windows, glass block entry. The grid of stripes is a variant on the grid of squares seen earlier. It is echoed in the bands of glass block over the entry, whose verticality is further emphasized by the unusual decision to turn the blue brick on end.

1631 W. Farwell, Rogers Park – opened in 1964. This site follows a familiar historical arc for the time period – in April 1963, a doctor living at this address passed away. In August, the “old house” and its lot went up for sale for $26,000. Thirteen months later, the new building was ready.

A particularly stylish example with multiple stepbacks as it moves back through its lot. It breaks with the others by banding its windows vertically. Lots of decorative activity, from the framed rectangles to smaller unframed squares, curly-cue canopy supports, and glass block at the stairwell.

The vertical bands of brick and glass block are nearly identical to those at 1535 Touhy, but banded and with plain clear block in addition to the colored geometric ones.

1918 W. Touhy Avenue, Rogers Park – opened 1966. It was under the same rental management as the previous building (1631 Farwell).

A much simpler example with banded windows and a grid of rectangles.

1615-17 W. Touhy, Rogers Park – Chicago. Doesn’t appear in the classifieds until 1971, which would make it rather a latecomer, but would also perhaps explain the unusual gabled roof.

Piers, banded windows (minus the limestone outlines), open rectangle at the entry, grid of unframed rectangles.

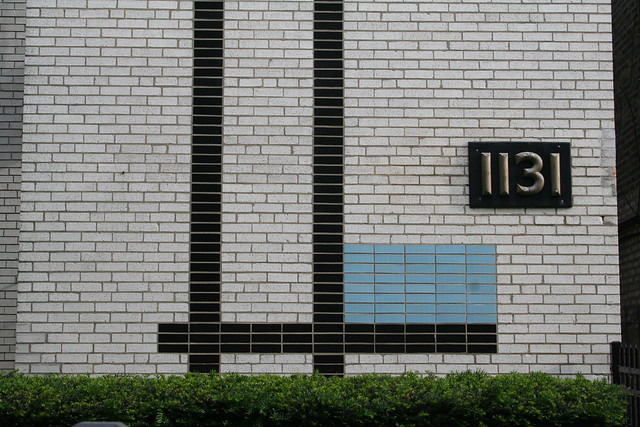

7555 N. Oakley Avenue, Rogers Park – Chicago. Open by 1965, M. Chapelski Construction Co. builders.

A dark-blue variant with simplified detailing, south of Howard Street. Piers, a stack of framed rectangles, banded windows.

7418 N. Oakley Avenue, Rogers Park -Inside, 6 apartments: three 1-bedrooms and three 2-bedrooms. No word on the builder, but in 1963 it was owned by the First National Bank of Skokie.

Very nearly the same building as the previous one, with the more common light blue accents, right down the street. Piers, banded windows, and framed rectangles recur from previous buildings; the vertical stripes on the side are new.

4744-46 N. Paulina, opened in 1967.

4744-46 N. Paulina, opened in 1967.

Folded canopy, corner piers, and the open rectangle. The lack of banding at the windows leaves the front facade feeling disjointed and ad hoc.

There are some buildings – again, around Rogers Park – which use the same decorative vocabulary, but in different shades of brick.

2700-2704 W. Pratt Avenue, West Ridge – Chicago. A 15-apartment building opened by 1967; builder David Schultz, who also built the blue-toned one across the street. Familiar elements include the piers, the grid of rectangles, and the open rectangles over the entries.

2001-2007 W. Touhy Avenue, Rogers Park – Chicago, open by 1968.

A third building by David Schultz; this one uses the piers, and the same sweatband/cross banding seen at 4850 N. Paulina. But that building was put up by a different company!

1844-1846 W. Birchwood Avenue – an 11-apartment building open by 1967; builder Sam Toporek Construction Company. Piers and the open rectangle.

1813-1819 W. Touhy Avenue, Rogers Park – Chicago. Open by 1966; builder: Sam Toporek Construction Company, same as the previous building. Piers, grid of rectangles, sweatband, open rectangle.

1534-1536 W. Farwell Avenue, Rogers Park – Chicago; opened by 1968. Builder: Louis Bender. Piers, grid of framed rectangles, open rectangle.

1623-27 W. Greenleaf Avenue, Rogers Park – Chicago. Piers, grid of unframed rectangles, open rectangle.

1538-40 W. Chase Avenue, Rogers Park – Chicago. Open by 1966; builder M. Chapelski Construction. Piers, grid of unframed rectangles, open rectangle.

1538-40 W. Chase Avenue, Rogers Park – Chicago. Open by 1966; builder M. Chapelski Construction. Piers, grid of unframed rectangles, open rectangle.

So, taking the open rectangle as a sample, we’ve got at least five different builders (Schultz, Bender, Luna, Chapelski, Toporek) using the same ornamental detail. Did they share an architect, or just an idea?

Returning to our color theme, there are plenty of blue-on-blondes which don’t use the distinctive design vocabulary outlined above. Some examples:

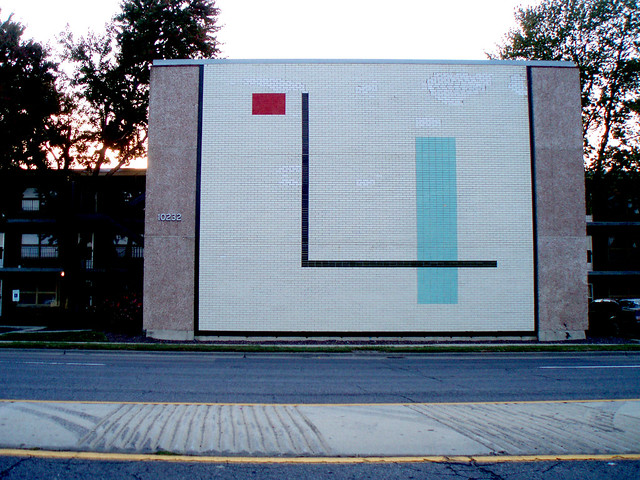

8308 Kilpatrick Avenue, Skokie IL

A suburban outlier that is also a design outlier, this building demonstrates how the features seen before aren’t necessary or unavoidable, but rather were intentional decisions. Here we have no corner piers, no glass block, no brick rectangles, and no banded window groups. Ornament is instead formed by raised vertical stripes and grids of single blue bricks between the windows. Is it merely chance that this building is far away from the others in both style and geography?

Here’s one more outlier, down in Berwyn:

Kenilworth Arms Apartments, 6850-54 W. Cermak Road, Berwyn – a 1959 building by George V. Jerutis & Associates builders.

This one uses the blue brick in a completely different way, framing and outlining windows groups with it. The white panels appear to be some kind of plaster or stucco, and might not be original.

Many other buildings beyond the core Rogers Park group use the same material palette and color scheme, though without the distinctive sense of style and fewer recurring design elements:

7744 N. Eastlake Terrace, Rogers Park – opened in 1963, advertised by Sunset Realty.

This elevator building features both vertically and horizontally banded windows; the entry is marked by glass block and a dimensional Flemish bond brick pattern. The little baseball cap brim overhang on the outer bays also hearkens back to the core group.

2155 W. Arthur Avenue, West Ridge – Chicago, south of Warren Park.

Awkward massing, but the horizontal bands of accent brick give it some style.

6117 N. Mozart Avenue – Chicago

This building limits itself to one big flashy move, as its blue brick window bands wrap around the most visible corner. Like almost all these buildings, the blue brick is laid in a stack bond rather than the running bond used on the common brick; here especially it adds some geometric punch to the fields of blue.

Lest you think all this is a given, or somehow obvious: there are some which are almost painfully dull, almost willful in their refusal to ornament beyond the bare minimum. What do you think of a building that only does the bare minimum?

1628 W. Touhy, Rogers Park – Chicago

1236 W. Touhy, Rogers Park – Chicago

5710 W. Lawrence Avenue, Portage Park – Chicago. Opened 1964. Vertical window bands, diamond patterned doors and not much else. The gabled roof looks bizarrely out of place, like it landed from another city.

Below are a trio of larger and slightly older buildings that used the blue-on-blonde color scheme before any of the previous buildings did. Naturally, like the no-effort ones above, they don’t follow the Rogers Park vocabulary, but they show the color scheme in a slightly earlier incarnation.

737 Ridge Avenue at Madison, Evanston – opened in 1960 as “Madison Tower Condominium”. It was meant to be condos, but was rented out as apartments, not going full condo until 1976. The developer at the time noted that the building was “a bit ahead of its time” regarding the then-new condo concept.

A rather dreadfully plain building, which uses blue glazed brick to infill the space between window bands in the projecting windows bays.

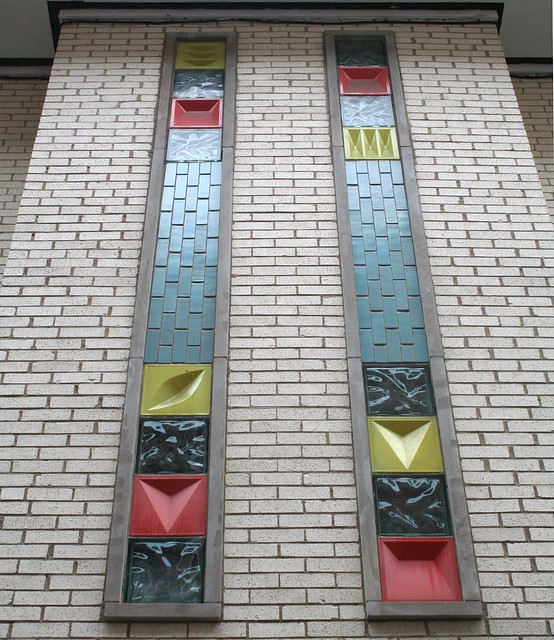

6107 N. Kenmore – today it’s the Sacred Heart Friary, home of the St. Bonaventure Province of Conventual Franciscans. In 1959 it opened as The Charleroi, an apartment building of 1 bedrooms and efficiencies advertised by Meister-Neiberg & Associates. It’s not clear when the friars moved in, but they renovated a ground-level space as a chapel, with small stained glass windows.

A blue accent at the corner, smaller blue accents at the entryway. The brick here is not stacked bond.

Kenmore Place, at 6012 N. Kenmore – a 4-Plus-1 near Loyola University. Appears to have opened 1958, which if correct would make it the oldest building in this set.

This one doesn’t even feature blue brick – just 1×1 mosaic tile in three bordered bands between the windows – but still follows the same color scheme to infill the space between windows in its large projecting bays.

You might think this is enough of a single color scheme to last a blog for a lifetime, but dear reader, you’d be mistaken. Tune in next week, when Blue on Blonde plugs in, sells out and goes commercial!