I photograph a lot of abandoned buildings, and have been doing so for somewhere between 15 and 20 years. I can’t say I’ve never found a romantic aspect to decay, nor can I deny finding architectural decay a fascinating subject for photography. The slow falling out of place of things, nature’s patient labor of unbuilding, creates visually rich patterns that naturally stir the soul and raise all manner of questions about the ultimately transient nature of our built world.

But photographing the ruination of the American cityscape has always had a social dimension for me. I consider it my ongoing and ever-present mission to document endangered architecture – to call attention to its plight, and to save its memory even if I can’t save its form. I haven’t always been disciplined about sticking to that principle, but I try. If I’m going to post a photo of building ruins, it better be because I want to call attention to that specific site, to a building’s history, to its architecture, its style, its neighborhood – something beyond just LOOK BUILDING FALL DOWN, I MAKE PURTY PICTURE.

In recent years, the popularization of “ruin porn” has given new dimensions to the ethical issues surrounding urban abandonment and decay, especially when considered in conjunction with the wide spread of urban gentrification. Alongside the earnest preservationists decrying the collapse of great buildings, a generation of urban explorers and their internet audience seems to revel in decay for its own sake. Again, I’ve been on a number of urbex jaunts myself, and can’t deny the fun and the thrill of it – but I try to come away with more than just pictures of stuff that’s falling apart.

The Internet is one big race to the bottom, though, and what was a niche culture ten years ago, shared on a few discussion boards, is today a vigorous source of clickbait for lowest common denominator sites like Buzzfeed and UpWorthy. Even this could have been used as a chance to educate and motivate, but instead these sites give us vapid headlines about the “strangely haunting beauty” of decay (or “beautiful and chilling images of abandonment”, or “the 30 most astounding abandoned places in the Solar System”, or whatever other collection of adjectives are making the rounds this week), which lead to isolated single images with minimal context. The state of things in ruin is treated as an aesthetic experience; people shake their heads, briefly wonder what the world’s coming to, and then click on with their lives.

Whichever way you choose to interpret the cultural and economic insanity that has allowed multitudes of fantastic American buildings to be abandoned and destroyed over the decades, there’s no shortage of photographs of the results online.

So when I decided to do a post on Chicago’s late, great Washburne Trade School, I had to stop and think for a moment. What am I trying to achieve here? Because at Washburne, decay – ludicrous, profligate, wasteful, narratively rich decay – was half the point.

I settled on two things as a focus:

1) Washburne was a cool building.

2) Washburne was full of insane crap.

In the process of illustrating these two points, I may include photographs of ruins. Hopefully they’re good photographs, and if they make the ruins look beautiful, well, don’t confuse a beautiful photograph with a beautiful state of affairs. Washburne should not have been abandoned, should not have been left to rot, and should not have been demolished – not in a sane world. Alas, our world is frequently certifiable, and Washburne is no longer with us.

Enough prelude! On with the show!

TREATISE #1: Washburne was a cool building

Washburne Trade School stood at the southwest corner of 31st and Kedzie. The school was contained in a massive complex of buildings, taking up the rough equivalent of three city blocks.

The historical basics: the buildings were originally home to the Liquid Carbonic Corporation plant, manufacturer of soda pop fizz. The huge red brick building with the classic Chicago tower dates to 1910 (architect: Nimmons & Fellows); the Streamline Deco office building to 1935 (architect: S.D. Gratias). The Chicago School District bought the buildings in 1958, spent a million bucks renovating them, and installed Washburne at the location, consolidating many programs in one place; there it stayed till it closed for good in 1996 (the school’s renowned chef training program survives as the Washburne Culinary & Hospitality Institute, part of the City College system.) The buildings were left abandoned until their 2008-09 demolition.

The primary building was a huge concrete structure with brick facing, with two long 4-story wings at a right angle. Where they met stood a tower with faintly Prairie School accents, of a style that can also be seen on a few Rogers Park apartment buildings (and probably elsewhere): horizontal bands of stone, square piers, shallow arches, and cubic volumes.

The rest of this marching monolithic mass of building, however, was pure Chicago School: concrete frame with brick cladding. Minimal ornament. Huge windows between narrow brick piers made up its bulk, and a simple overhanging roof element capped it off without elaboration.

To the west, a totally prosaic annex was tacked on in 1936 for bottling machinery assembly and metalwork; I never photographed it intact, but Google Streetview shows it to be an unremarkable concrete frame infilled with industrial windows.

To the east, the school was connected by two skybridges to the former Liquid Carbonic Corporation office building, a Streamline Deco edifice with an inwardly-curved main entryway (echoed by a more modest building across the street that survives to the present.)

THE Liquid Carbonic Corporation

The Streamline building was already 2/3rds gone when I arrived on the scene in 2008 – but by chance, I’d snapped a few shots of it while driving by in 2005, while it was still intact.

An expansive garage stood on the block-interior side of the main building, gone before I ever got there; its outline appears on the main building.

This was classic Chicago School architecture, as Preservation Chicago notes – impressive for its size, for its architectural purity, for its unabashed hugeness. Not as famous or glamorous as the skyscrapers of the Loop, buildings like Washburne nonetheless made Chicago what it was and is – a sprawling hub of manufacturing, a modern city that sprang up out of nothing and spread like wildfire across the prairie. They were landmarks of their neighborhoods, sources of jobs, and iconic images for the city. With huge windows, concrete structures and open floor plans, they should lend themselves readily to adaptive reuse – but they have fallen in alarming numbers.

The Washburne buildings were demolished because… well, nobody seemed to have a good answer at the time. The ol’ E-word was apparently batted around some – you can justify tearing down anything you don’t like by calling it an “eyesore”, and you can justify calling it an eyesore basically if anything at all is wrong with it, regardless of how simple it would be to fix it. Broken windows? EYESORE! Tear it down, quick! (And pray nobody ever breaks a window on your house.)

Another driving factor was desire for green space. Normally I lobby against this desire tooth and nail, because most American cities have far too much green space, not too little – but Little Village actually does need a park. And they will get one – just… not on the Washburne site, it turns out. A huge brownfield site designated Park No. 553 – closer to a sizable residential population, incidentally – will instead be turned into public green space.

In fact, the Washburne site is still sitting vacant five years after the demolition was finished.

Saint Anthony Hospital has stepped with a pretty fantastic program for the site, announced in 2012 – an 11 story hospital building, some smaller wellness-related buildings, some retail, and a modest public park. It is as good a project as anybody could want for such a site – urban, modern, dense, mixed use, integral to the community – and it’s an economic engine that will likely offer spillover benefits to the area around it. The city is well on board and a design team was announced last year; hopefully further progress will follow soon.

Seriously, look at the light in that room. Magnificent. Who wouldn’t want that?

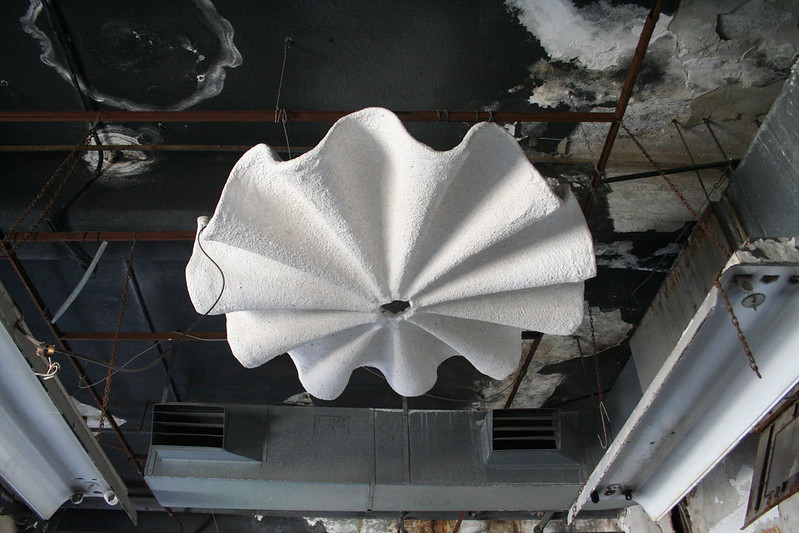

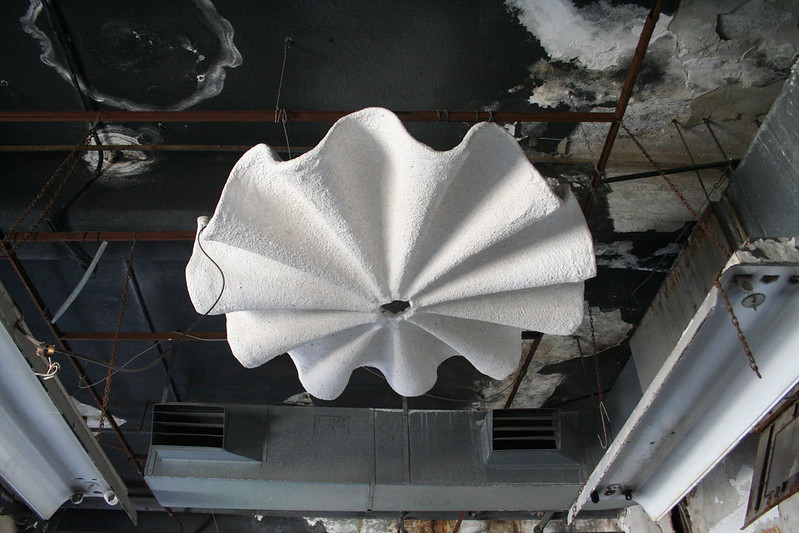

TREATISE THE SECOND: Washburne was full of insane crap.

I mean it. The school’s buildings were absolutely loaded to the hilt with crazy, wacky, random, quirky stuff, the likes of which you’ve never seen in all your life. Visiting it was a non-stop stream of “what the hell?” moments.

Some of it was bizarre by virtue of age. With a history on the site going back to 1958, some of the materials had become quite dated by the time the school closed. Even the most modern of equipment would have been over a decade old by the time the building came down, but everything left behind was likely quite a bit older.

1970s style font

1960s style sign

Gloriously dated curtains

Other portions are just strange by virtue of being inside a classroom. Framed-up mini-buildings, random plasterwork, set-like storefronts lining the hallways, disassembled automobiles, massive saws, metalworking machines – the range of things found inside a trade school is massive.

Odd juxtopositions abound as students practiced their craft using the building as a test subject. You never knew what style or material of decoration you might find in a room or a hallway.

Again, not to romanticize decay, but… the abandoned site was a big ol’ playground for any number of urban adventurers, and part of me is sad over its loss for that reason alone. Explorers of all stripes – taggers, architects, photographers, historians, urbexers, perhaps an odd New Years Eve celebrant or two – wandered the rotting hulk, leaving their mark or documenting their passage.

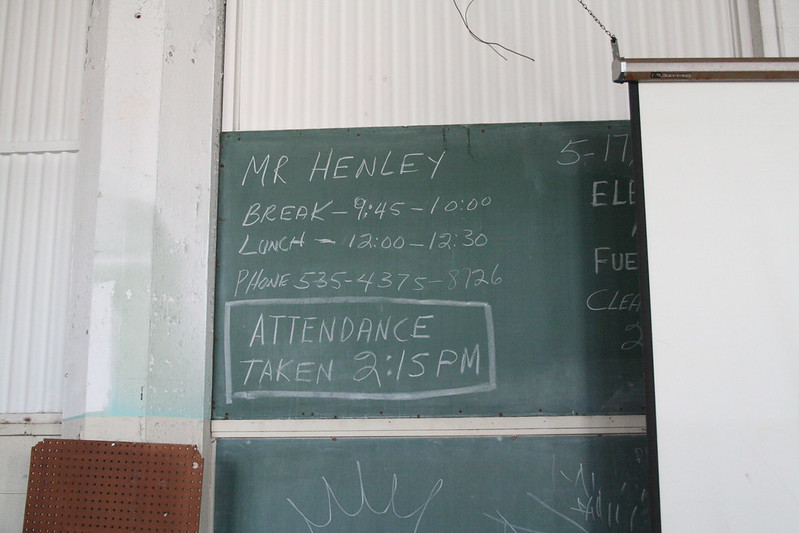

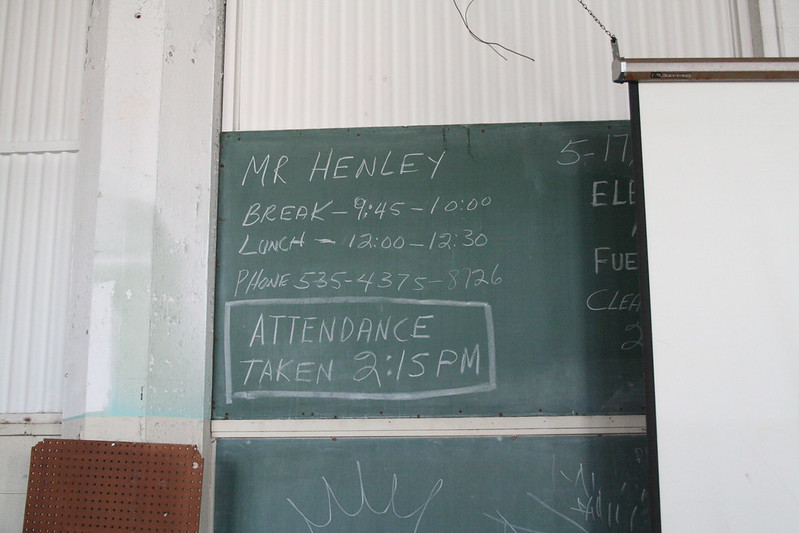

And finally, there’s just the volume of stuff left behind in the building. Chairs, desks, equipment, lockers, projects, cabinets, shelves, machinery, hardware, tables, signs, posters, pamphlets, books, computers – a huge amount of paraphernalia was simply left where it stood. Other explorers, arriving sooner, found even more, some of which they carried out with them.

Mr. Henley didn’t even bother to erase the blackboard! (And what kind of phone number is that? And how long is this class, anyways?)

No home for a circa-1970 PA system in a new school? Blasphemy!

Of course, when you think about it, the motivation to bring a lot of it along to a new location is pretty lacking. New building usually equals new equipment, and anyway, plenty of the stuff was heavily dated by the time Washburne closed. There’s no telling how much gear did leave the building along with its occupants.

Forgotten Chicago has a terrific post on the opening and the closing of Washburne, with a lot more historical detail than what I’ve posted. A simple Google search will also bring up plenty more photos of the school’s dilapidated interior in the years before was razed – amazingly, I’ve barely scratched the surface here. Thanks to Chicago’s prolific architectural exploration community, you can still spend hours wandering the halls of this lost landmark in digital form.